When a CNC part comes off the machine, its surface is more than a visual outcome of cutting tools and toolpaths. That surface directly affects how the part behaves in service. Friction, wear, corrosion resistance, sealing reliability, and fatigue life are all influenced by surface condition. In many applications, the surface finish plays just as critical a role as material choice or dimensional accuracy. Treating finishing as a cosmetic step often leads to premature failures, assembly issues, or unnecessary costs.

Surface Finishes for CNC Machining

This article is to look at surface finishing after CNC machining from a functional point of view. Instead of defaulting to polishing, anodizing, or passivation based on habit or appearance, this guide helps engineers, designers, and buyers choose finishes that match real performance needs.

Why Surface Finishing Matters for Part Function

Surface finishing is often discussed after machining is complete, but in practice, it has a direct impact on how a part performs in service. The surface left by CNC machining is not neutral. Tool marks, micro grooves, and localized stresses all influence friction, corrosion behavior, and long-term durability. Even when a part meets dimensional tolerances, surface condition can determine whether it performs reliably or fails early.

Key functional impacts of machined surfaces

One of the most immediate effects of surface finish is its influence on friction and wear. Rougher surfaces increase asperity contact, which raises friction and accelerates wear. Smoother surfaces generally reduce friction, but they also change how lubrication films form and behave.

Key performance factors influenced by surface condition include:

- Friction and wear behavior

Surface roughness controls contact area, heat generation, and wear rate in sliding or rotating interfaces.

- Fatigue life and crack initiation

Tool marks act as micro stress raisers. Under cyclic loading, cracks often initiate at these locations, reducing fatigue life.

- Corrosion pathways and contamination risk

Surface grooves and torn material can trap moisture, chemicals, and debris, creating localized corrosion sites.

- Fit, sealing, and mating reliability

Surface texture affects how well parts seat, seal, and maintain consistent contact over time.

Each of these factors becomes more critical as loading increases, tolerances tighten, or environments become more aggressive.

Functional examples across common applications

The role of surface finishing becomes clearer when looking at specific use cases. In rotating systems such as bearings and shafts, surface finish directly affects noise, wear, and operating temperature. A shaft may be dimensionally correct, but visible tool marks can disrupt lubrication and lead to premature bearing damage.

In fluid-handling components, surface condition influences both flow and sealing. Valve seats, pump housings, and sealing faces often require controlled finishes to prevent leakage and erosion. Rough internal surfaces can disturb flow patterns and increase pressure drop, particularly in high-velocity or abrasive fluids.

Different part categories place different demands on surface finish:

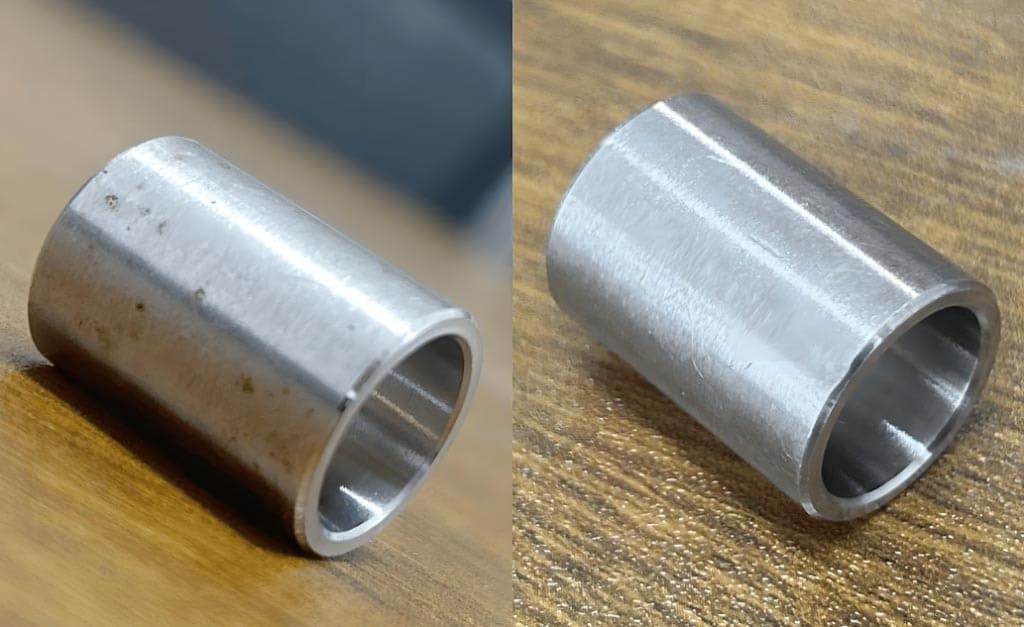

- Sliding and rotating components such as shafts, bushings, and guides rely on controlled roughness for wear and lubrication stability.

- Fluid-facing surfaces require finishes that support sealing and minimize turbulence or material loss.

- Structural parts often prioritize fatigue resistance and corrosion control rather than low friction.

- Cosmetic components focus on visual quality, but still require attention to hidden functional risks.

Understanding which category a surface belongs to helps prevent unnecessary or ineffective finishing.

When a raw machined finish is acceptable

In many applications, an as-machined surface is fully sufficient. Parts that operate in stable, dry environments and experience low cyclic loads often perform reliably without additional finishing. Typical examples include brackets, fixtures, mounting plates, and internal structural components.

Leaving surfaces as-machined can offer practical benefits:

- Preserves tight dimensional control

- Reduces lead time and processing cost

- Eliminates variability introduced by secondary operations

When possible, avoiding unnecessary finishing improves consistency and simplifies production.

When finishing becomes mandatory

There are also situations where surface finishing is essential rather than optional. Parts exposed to corrosive environments, repeated loading, or hygiene requirements typically require additional surface treatment to meet performance or regulatory expectations.

Finishing is usually required when:

- The part operates under cyclic or fatigue-critical loading

- The surface must seal against fluids or gases

- Corrosion resistance is critical to service life

- Regulatory standards apply, such as medical or food-contact requirements

In these cases, surface finishing is a functional engineering decision. The goal is not appearance, but controlled surface behavior over the entire lifecycle of the part.

Polishing and Mechanical Finishing: When Smoothness Is Critical

Polishing and other mechanical finishing processes are often selected with the assumption that smoother is always better. In reality, polishing changes how a surface behaves mechanically, chemically, and dimensionally. While it can significantly improve performance in certain applications, it can also introduce problems if applied without a clear functional reason. Understanding what polishing actually changes is essential before specifying it on a drawing or purchase order.

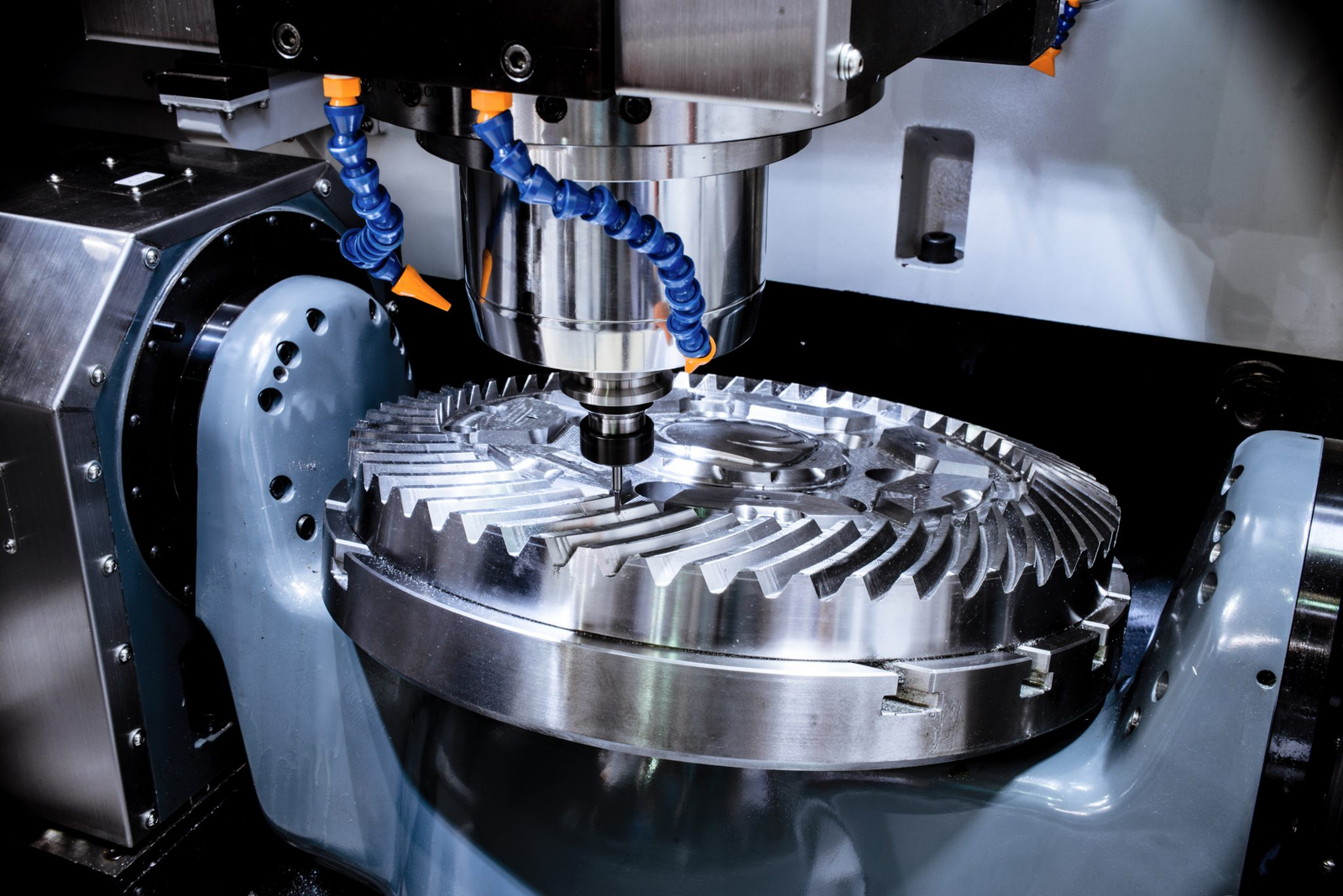

CNC Machining Parts Polishing Process

Mechanical finishing should be viewed as a targeted process. It is most effective when the role of the surface is clearly defined, such as reducing friction, improving cleanability, or controlling contact behavior. When used blindly, it can reduce part reliability or hide deeper machining issues that should have been addressed earlier.

What polishing and buffing actually change

Polishing primarily modifies surface topography rather than bulk material properties. Removing peaks left by machining reduces surface roughness and alters how surfaces interact under load. This change affects contact mechanics, lubrication behavior, and local stress distribution.

From a functional standpoint, polishing influences several key surface characteristics:

- Surface roughness reduction

Polishing lowers Ra and related roughness parameters by removing tool marks and surface asperities. This improves smoothness but also reduces the ability of a surface to retain lubricants in some applications.

- Contact behavior and friction

Smoother surfaces generally reduce friction during sliding contact. However, extremely smooth finishes can lead to boundary lubrication issues or stick-slip behavior if not properly designed.

- Stress concentration at tool marks

Removing sharp machining grooves reduces localized stress risers. This can improve fatigue performance in parts subjected to cyclic loads, provided tolerances are maintained.

It is important to note that polishing does not correct geometric errors. Flatness, roundness, and alignment issues remain unchanged unless material removal is tightly controlled.

Best fit applications for polished surfaces

Polishing provides the most value when surface interaction directly affects performance, safety, or cleanliness. In these cases, the benefits outweigh the added cost and processing risk.

Polished finishes are commonly specified for:

- Medical, food-contact, and hygienic components

Smooth surfaces reduce bacterial adhesion and make cleaning more effective. Polishing helps meet regulatory and cleanliness standards where surface contamination cannot be tolerated.

- Visible or optical components

For parts where appearance matters, polishing improves visual quality and perceived value. This includes consumer-facing products and architectural components.

- Sliding and mating surfaces

Bushings, guides, and sealing interfaces often benefit from controlled smoothness to reduce wear and ensure consistent contact during motion.

In these applications, polishing is chosen to support a clear functional outcome rather than simply improve appearance.

Common pitfalls in mechanical finishing

One of the most frequent issues with polishing is unintended material removal. Excessive polishing can alter critical dimensions, especially on tight-tolerance features. Even small changes can affect fit, alignment, or performance in precision assemblies.

Other common risks include:

- Rounding of sharp edges

Polishing tends to soften edges and corners, which can compromise functional geometry such as sealing edges or datum features.

- Masking machining defects

Surface polishing can hide chatter marks, tool wear, or improper feeds rather than addressing the root cause during machining.

- Inconsistent surface quality

Manual or poorly controlled polishing processes can lead to variation from part to part, reducing repeatability.

These issues often arise when polishing is treated as a corrective step instead of a planned process with defined limits.

Anodizing and Conversion Coatings: Protection with Side Effects

Anodizing is often selected because it is widely known as a durable and corrosion-resistant finish for aluminum parts. While these benefits are real, anodizing also changes the surface in ways that affect dimensions, wear behavior, and long-term reliability. Treating anodizing as a simple protective coating can lead to unexpected problems, especially on precision components.

To use anodizing correctly, it must be understood as a controlled surface transformation rather than a cosmetic layer. The process modifies the aluminum surface itself, which brings clear advantages but also introduces design and manufacturing constraints that must be considered early.

What anodizing actually provides

Anodizing creates an oxide layer that is integrated with the aluminum substrate. Unlike applied coatings, this layer grows both outward and inward from the original surface. As a result, anodizing improves several functional properties while also altering surface geometry.

The most important functional benefits include:

- Improved corrosion resistance

The anodic oxide layer protects aluminum from oxidation and chemical attack, particularly in outdoor and humid environments.

- Increased surface hardness

Anodized surfaces are harder than bare aluminum, which improves resistance to abrasion and light wear.

- Electrical insulation

The oxide layer is non-conductive, which can be useful in applications where electrical isolation is required.

These properties make anodizing attractive for structural and environmental protection, but they do not make it suitable for every surface on a part.

When anodizing works best

Anodizing is most effective on aluminum components where corrosion resistance and surface durability matter more than tight dimensional control. Structural parts, housings, and external components often benefit from anodizing without significant risk.

Typical applications where anodizing performs well include:

- Aluminum structural components

Frames, brackets, and enclosures that require environmental protection but do not rely on precise fits.

- Wear-exposed but non-precision surfaces

Surfaces that see handling or light abrasion but are not part of sliding or sealing interfaces.

- Outdoor and marine environments

Anodizing helps protect aluminum parts from moisture, salt exposure, and UV-related degradation.

In these cases, the functional benefits of anodizing outweigh its limitations, provided the process is properly controlled.

Dimensional and tolerance considerations

One of the most overlooked aspects of anodizing is thickness buildup. Because the oxide layer grows partially into the base material, finished dimensions change. This can affect fits, clearances, and mating relationships if not accounted for during design.

Critical dimensional issues include:

- Thickness buildup on precision features

Holes, slots, and bearing surfaces can shrink beyond tolerance after anodizing.

- Threaded features

Threads may bind or lose engagement if the anodizing thickness is not controlled or masked.

- Tight-tolerance assemblies

Parts designed at nominal size without allowance for anodizing often fail to assemble correctly.

To avoid these problems, designers must specify dimensional allowances and identify surfaces that require masking or post-processing.

Passivation and Chemical Finishes: Cleaning vs Coating

Passivation is often grouped together with surface coatings, but functionally, it serves a very different purpose. Unlike anodizing or plating, passivation does not add a new layer or change dimensions. Instead, it improves corrosion resistance by cleaning and stabilizing the existing surface. This distinction is critical, especially for precision components where dimensional integrity cannot be compromised.

In CNC machining, stainless steel parts are particularly vulnerable to surface contamination. Cutting tools, fixturing, and handling can introduce free iron and other residues onto the surface. Passivation addresses this problem by removing contaminants and allowing the material’s natural corrosion resistance to perform as intended.

What passivation does and does not do

Passivation works through controlled chemical treatment, typically using nitric or citric acid solutions. The process dissolves free iron and other contaminants from the surface without attacking the base metal when done correctly.

Functionally, passivation provides several key benefits:

- Removal of free iron contamination

Machining and handling can deposit iron particles that become corrosion initiation sites. Passivation eliminates these residues.

- Enhanced corrosion resistance

By cleaning the surface, passivation allows the stainless steel to form a stable and continuous chromium oxide layer.

- Preservation of dimensional accuracy

Because no coating is added, part dimensions and tolerances remain unchanged.

At the same time, it is important to understand the limitations of passivation. It does not increase surface hardness, improve wear resistance, or hide machining defects. Expecting passivation to compensate for poor surface quality is a common and costly mistake.

Best applications for passivated surfaces

Passivation is most effective on precision components where corrosion resistance is required without altering geometry. This makes it especially valuable in industries with strict performance and regulatory requirements.

Typical applications include:

- Stainless steel precision parts

Components with tight tolerances, such as shafts, fittings, and fasteners.

- Medical, aerospace, and food-related equipment

Applications where cleanliness, corrosion resistance, and material integrity are critical.

- Components with complex geometry

Parts where coating buildup would create fit or assembly problems.

In these cases, passivation improves surface stability while maintaining the original machined form.

Importance of pre-cleaning and surface preparation

Passivation is not a substitute for proper machining or cleaning. Oils, coolants, and embedded debris must be removed before chemical treatment. If contaminants remain, the passivation process becomes inconsistent and less effective.

Key preparation steps often include:

- Thorough degreasing to remove machining oils

- Rinse to eliminate residues from cleaning agents

- Inspection for embedded debris or surface damage

Skipping or rushing these steps increases the risk of uneven corrosion resistance or post-process staining.

Choosing the correct chemistry for the alloy

Not all stainless steels respond the same way to passivation. Alloy composition, heat treatment, and prior processing influence how the surface reacts to different chemical solutions. Selecting the wrong chemistry can reduce effectiveness or damage the surface.

Common issues arise when:

- Nitric-based processes are applied to sensitive alloys without proper control

- Citric-based processes are used without adequate validation

- Mixed alloy batches are processed together without segregation

Clear identification of material grade and controlled processing parameters is essential for consistent results.

Common misconceptions and mistakes

One of the most frequent misunderstandings is assuming passivation improves surface finish or hides machining flaws. In reality, any surface defects present before passivation will remain visible afterward.

Other common mistakes include:

- Treating passivation as optional for stainless steel parts

- Using it as a corrective step after poor machining practices

- Failing to verify corrosion resistance through testing

When used correctly, passivation is a preventative measure, not a repair process.

Passivation plays a subtle but critical role in surface finishing. It protects precision parts without altering their geometry, but only when applied with proper preparation and material knowledge. In the next section, we will bring all finishing options together and build a practical framework for selecting the right surface finish based on function, risk, and cost.

Choosing the Right Finish: Best Practices and Decision Framework

Selecting a surface finish should never be a default decision. Each finishing process changes how a surface behaves, introduces certain risks, and adds cost. The most reliable parts are usually the result of deliberate choices made early in design, not last-minute finishing decisions made to improve appearance or meet vague specifications.

A practical approach to surface finishing starts by clearly defining what each surface on a part is expected to do. Once the function is understood, it becomes much easier to eliminate unnecessary options and focus on finishes that provide real value.

Questions to ask before selecting a finish

Before specifying any finishing process, it is important to evaluate the role of the surface within the assembly and its operating environment. This step prevents overprocessing and helps avoid finishing steps that conflict with functional requirements.

Key questions that guide finish selection include:

- What function does the surface serve?

Determine whether the surface is structural, load-bearing, sliding, sealing, or purely cosmetic.

- Is corrosion, wear, or friction the main concern?

Different finishes address different failure modes. Identifying the primary risk helps narrow the options.

- How tight are the tolerances?

Finishes that add thickness or remove material can affect fit and alignment.

- Is the surface visible or hidden?

Cosmetic requirements should not drive finishing choices for functional surfaces unless appearance is critical.

Answering these questions early reduces design changes and rework later in production.

Separating functional and cosmetic surfaces

One of the most effective ways to control finishing cost and risk is to separate cosmetic surfaces from functional ones. Not every surface on a part requires the same level of finishing.

Best practices include:

- Applying cosmetic finishes only where appearance matters

- Protecting functional surfaces from unnecessary processing

- Using masking or selective finishing when different surfaces require different treatments

This approach allows designers to achieve visual quality without compromising performance-critical features.

Conclusion

Surface finishing after CNC machining is not a final cosmetic step. It is a functional engineering decision that directly influences how a part performs, how long it lasts, and how reliably it operates in real conditions. Polishing, anodizing, and passivation each address different surface-related risks, from friction and wear to corrosion and contamination. When these processes are applied with a clear understanding of surface function, they strengthen part performance. When applied by habit, they often introduce hidden problems.

The most effective finishing strategies start with intent. By understanding how each surface interacts with loads, environments, and mating components, engineers and buyers can choose finishes that add real value while avoiding unnecessary cost and risk. Selecting the right finish is not about making parts look better. It is about ensuring that every surface supports the part’s purpose throughout its entire service life.