CNC machining supports both rapid prototyping and full-scale production, but the way it is used changes significantly between these two stages. In prototyping, the goal is speed. Teams focus on validating form, fit, and function as quickly as possible, often accepting compromises that would not be acceptable in a finished product.

When the same part moves into production, priorities shift. Consistency, cost efficiency, surface quality, and long-term reliability become critical. Approaches that work well for prototypes can create problems at scale if they are not adjusted. Understanding what changes between CNC machining for rapid prototyping and production runs helps teams reduce rework, control costs, and move to market with fewer delays.

Purpose & Priorities: Prototype vs. Production Mindset

CNC machining serves very different purposes during prototyping and production, even though the same machines and materials may be used. At the prototype stage, the focus is on learning. Speed, flexibility, and the ability to make changes matter more than efficiency. Once a design moves into production, the mindset shifts toward stability, repeatability, and cost control. Understanding this shift is essential to avoid carrying prototype decisions into a production environment where they no longer make sense.

The biggest difference lies in how teams define success at each stage. Prototyping rewards fast answers, while production rewards predictable outcomes.

Rapid Prototyping Goals

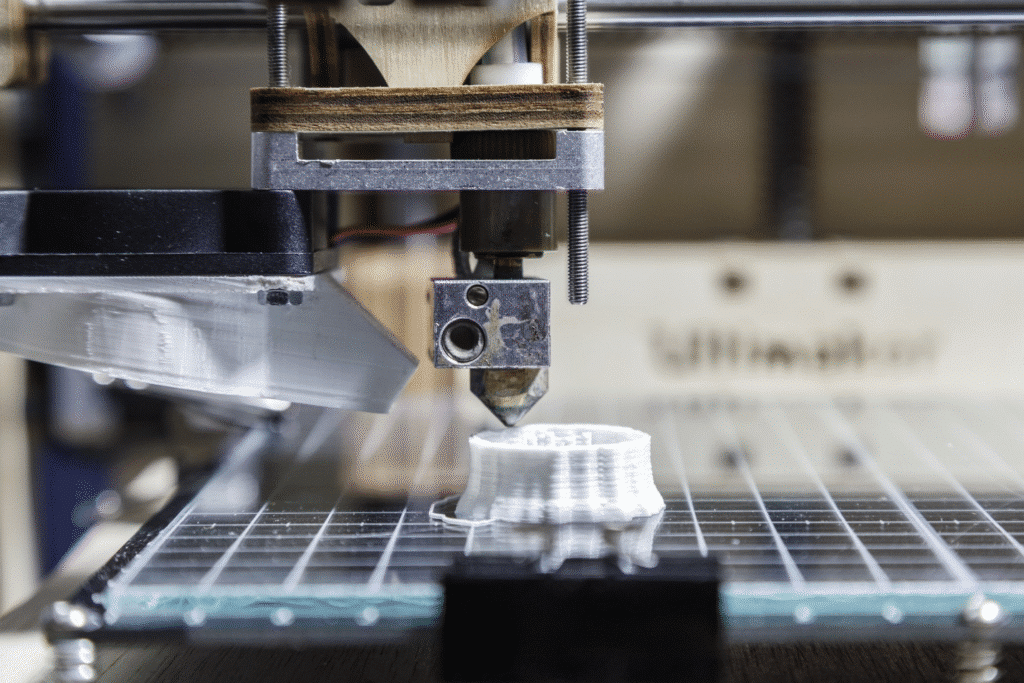

During rapid prototyping, CNC machining is used as a validation tool. The objective is not perfection, but confirmation that the design works as intended.

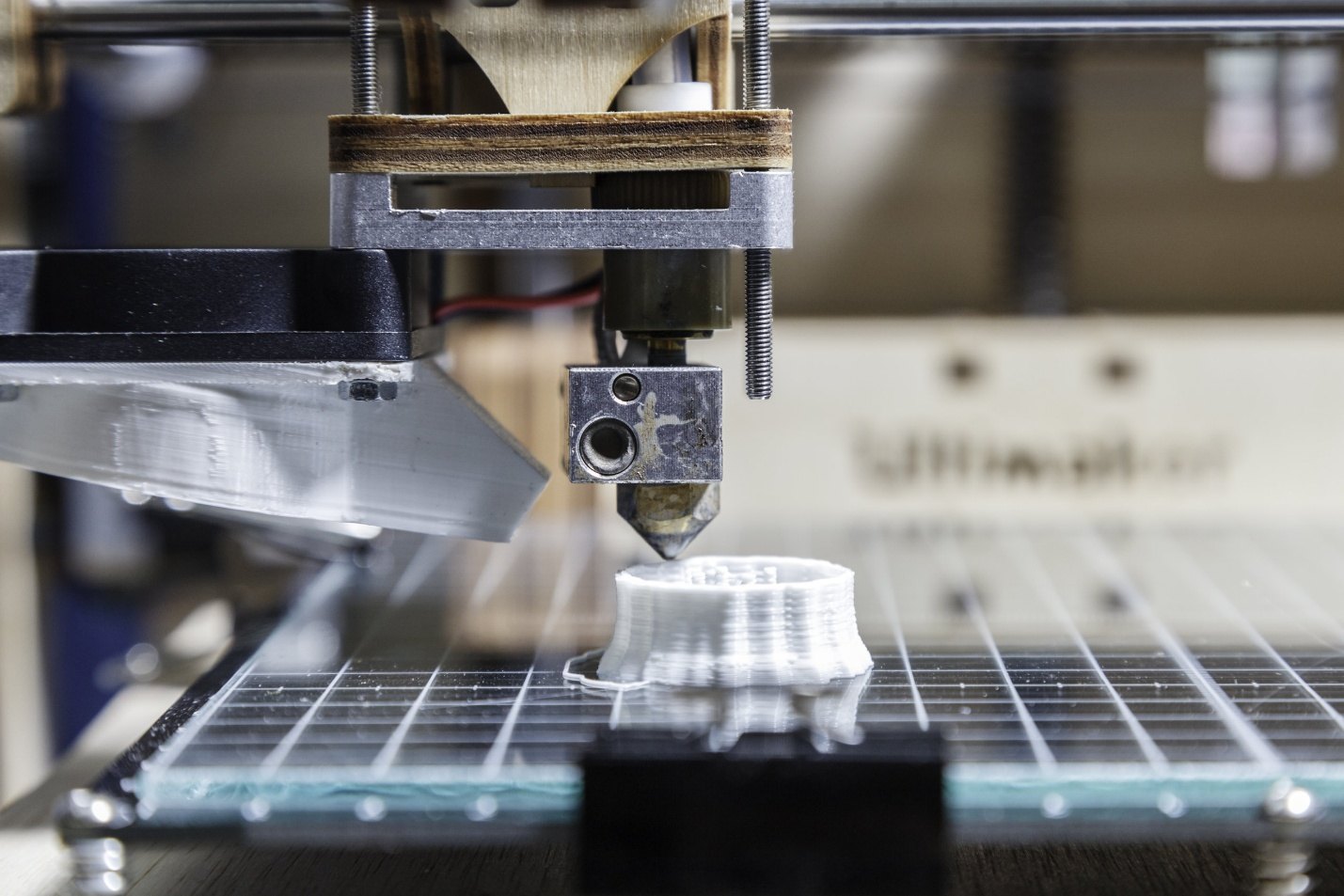

CNC Machining for Rapid Prototyping

Key priorities at this stage include:

- Fast turnaround to support design iteration

- Flexibility to accommodate frequent design changes

- Validation of form, fit, and basic function

- Minimal setup time and simplified machining strategies

Parts may be machined with conservative tool paths or oversized features to reduce programming effort. Surface finish and tight tolerances are only addressed when they directly affect function. If a part proves the concept and highlights design issues early, it has done its job.

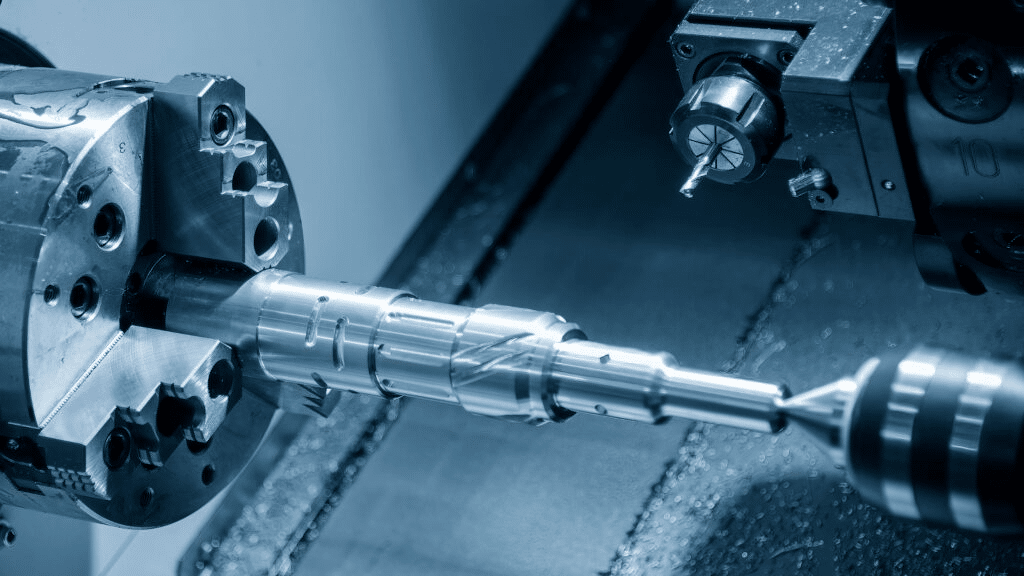

Production Run Goals

In production, CNC machining becomes a manufacturing process rather than a learning tool. The goal is to produce the same part repeatedly with consistent quality and minimal variation.

Production priorities typically include:

- Repeatability across batches and machines

- Reduced cycle time and lower unit cost

- Stable processes that minimize scrap and rework

- Long-term reliability in both machining and part performance

At this stage, even small inefficiencies become expensive. Tool paths, feeds, and speeds are refined to balance quality and throughput. Any feature that causes inconsistency or excessive machining time is closely examined and often redesigned.

Design Intent Across Stages

Design intent evolves as a product moves from prototype to production. Early-stage designs often prioritize functionality over manufacturability. Features may be thicker, radii may be generous, and tolerances may be loosely defined to ensure the part can be machined quickly.

As the design matures, geometry is refined with production in mind. Wall thickness is optimized, unnecessary material is removed, and features are adjusted to improve tool access and reduce cycle time. What was acceptable as a temporary solution in a prototype may become a liability in production if it increases machining complexity.

Engineering Trade-offs

One of the hardest decisions teams face is knowing when to prioritize speed over manufacturability. In prototyping, fast turnaround often justifies inefficient tool paths or extra material. In production, those same choices lead to higher costs and longer lead times.

Experienced teams treat prototyping and production as related but distinct phases. They use prototypes to learn quickly, then intentionally revisit design and process decisions before scaling. This mindset reduces friction during the transition and prevents production from inheriting problems that were never meant to be permanent.

Tolerances: From Flexible to Controlled

Tolerance requirements change significantly when moving from rapid prototyping to production machining. In the early stages, tolerances exist mainly to support functionality and basic assembly checks. As production begins, tolerances become a critical control mechanism that affects cost, quality, and long-term performance. Treating tolerances casually during scale-up is one of the most common sources of scrap and rework in CNC manufacturing.

The shift is not only about tighter numbers on a drawing. It reflects a change in how accuracy is achieved, measured, and maintained across multiple parts and batches.

Prototype Tolerances

During prototyping, tolerances are typically kept wide unless a specific feature demands precision. The objective is to prove the concept, not to lock down final dimensions.

Prototype tolerance practices often include:

- General tolerances are applied across most features

- Manual adjustments on the machine to achieve an acceptable fit

- Limited concern for dimensional drift between parts

- Acceptance of minor deviations that do not affect function

This approach allows parts to be produced quickly with minimal setup and inspection time. Engineers often use prototypes to identify which dimensions truly matter and which ones can be relaxed later.

Production Tolerances

In production, tolerances directly impact assembly consistency, performance, and customer acceptance. Tight or poorly defined tolerances increase risk and cost if the process is not capable of holding them consistently.

Production tolerance requirements typically involve:

- Feature-specific tolerances based on function and interface needs

- Controlled machining processes with repeatable tool paths

- Defined datum structures to ensure consistency

- Clear distinction between critical and non-critical dimensions

Every tolerance must be achievable within the process capability. If a tolerance cannot be held repeatedly without excessive adjustment, it becomes a liability rather than a quality control tool.

Cost Implications of Tight Tolerances

Tighter tolerances increase cost in multiple ways. Machining time increases as tools take lighter passes to maintain accuracy. Tool wear becomes more critical, and setups require more attention to alignment and stability.

Additional cost drivers include:

- Increased inspection time per part

- Higher scrap rates if processes drift

- Slower throughput due to conservative machining parameters

For production runs, unnecessarily tight tolerances often provide no functional benefit while significantly increasing unit cost. Experienced teams review every tight tolerance to confirm that it is truly required.

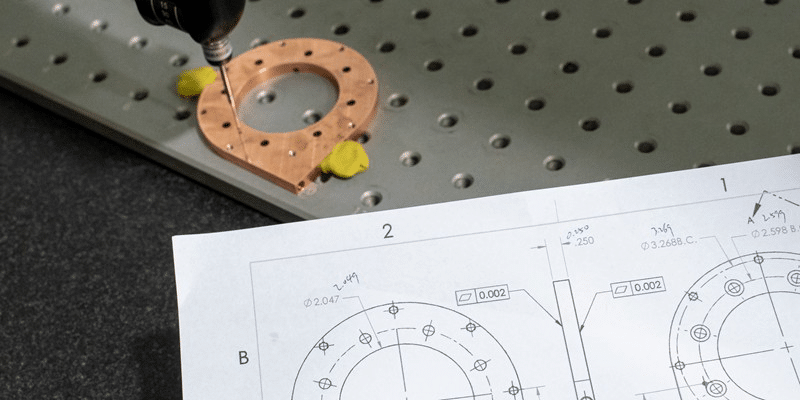

Metrology and Inspection Approach

Inspection requirements evolve alongside tolerance control. Prototypes are usually checked with basic measuring tools such as calipers, micrometers, or simple gauges. The goal is to confirm that the part generally matches the design intent.

Production parts require a more structured inspection strategy. This may include:

- First article inspection reports

- Coordinate measuring machine verification

- In-process checks to monitor dimensional drift

- Statistical process control for critical features

Inspection in production is not just about catching defects. It is about proving that the machining process remains stable over time. This shift in metrology reflects the broader transition from experimentation to controlled manufacturing.

Surface Finish Expectations & Material Choices

Surface finish and material selection often receive limited attention during early prototyping, but they become critical as parts move toward production. In prototypes, finish and material are usually chosen to support quick validation. In production, both directly affect performance, durability, appearance, and cost. Failing to adjust expectations at this stage can lead to quality issues and unexpected secondary operations.

As volumes increase, even small inconsistencies in finish or material behavior can create downstream problems in assembly, coating, or field performance.

Prototype Surface Finish Expectations

Prototype parts are typically machined with practical, time-efficient finishes. Unless a surface plays a functional role, visual appearance is rarely a priority.

Common prototype finish characteristics include:

- Tool marks left from standard roughing and finishing passes

- Limited use of secondary finishing operations

- Focus on functional surfaces only

- Acceptance of variation between parts

This approach allows engineers to evaluate fit and function quickly without investing time in cosmetic refinement. If a surface does not affect testing results, it is often left as-machined.

Production Surface Finish Requirements

Production parts require controlled and repeatable surface finishes. These finishes may affect sealing, wear, appearance, or downstream processes such as coating or bonding.

Production finish requirements often include:

- Defined Ra or Rz values on critical surfaces

- Consistent visual appearance across batches

- Planned secondary operations such as polishing or blasting

- Surface preparation for anodizing, painting, or coating

Achieving a consistent surface finish in production requires stable tooling, controlled cutting parameters, and proper tool maintenance. What looks acceptable on a single prototype may not be acceptable when multiplied across hundreds of parts.

Material Selection for Prototypes

Prototype materials are often chosen for speed and machinability rather than final performance. Engineers may select materials that cut easily and are readily available.

Typical prototype material choices include:

- Free-machining aluminum alloys

- Standard engineering plastics

- Low-cost metals that approximate final properties

These materials allow rapid iteration and reduce tool wear. However, they may not accurately represent thermal behavior, strength, or surface response of the final material.

Material Selection for Production

Production materials must meet functional, regulatory, and environmental requirements. Strength, fatigue life, corrosion resistance, and long-term stability become non-negotiable.

Production material decisions often consider:

- Mechanical and thermal performance in real-use conditions

- Compliance with industry standards

- Consistency across suppliers and batches

- Machining behavior at scale

Switching materials late in the process can affect tolerances, surface finish, and cycle time. For this reason, experienced teams test critical features in production-grade materials before final release.

Optimization and Transition Timing

The transition from prototype materials and finishes to production-grade options should be intentional. Rushing this decision can lock in inefficient processes or mask issues that appear only at scale.

A controlled transition typically involves:

- Machining late-stage prototypes in final materials

- Validating surface finish requirements under production conditions

- Adjusting tool paths and parameters to suit material behavior

- Reviewing cost impact before committing to volume

By aligning material and finish decisions with production goals early, teams reduce the risk of surprises during ramp-up and maintain control over quality and cost.

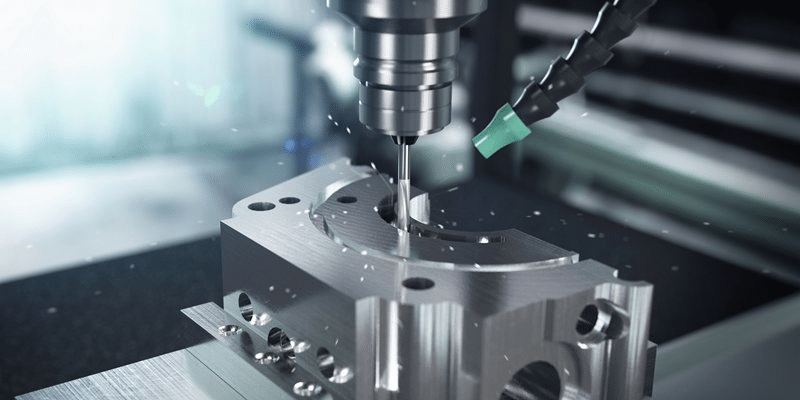

Tooling Investment & Process Stability

Tooling strategy is one of the clearest indicators of whether a CNC process is set up for prototyping or production. In prototyping, tooling decisions favor flexibility and speed. In production, tooling becomes an investment aimed at reducing cycle time, improving consistency, and protecting quality over long runs. The shift requires careful planning because tooling choices directly affect cost, lead time, and process reliability.

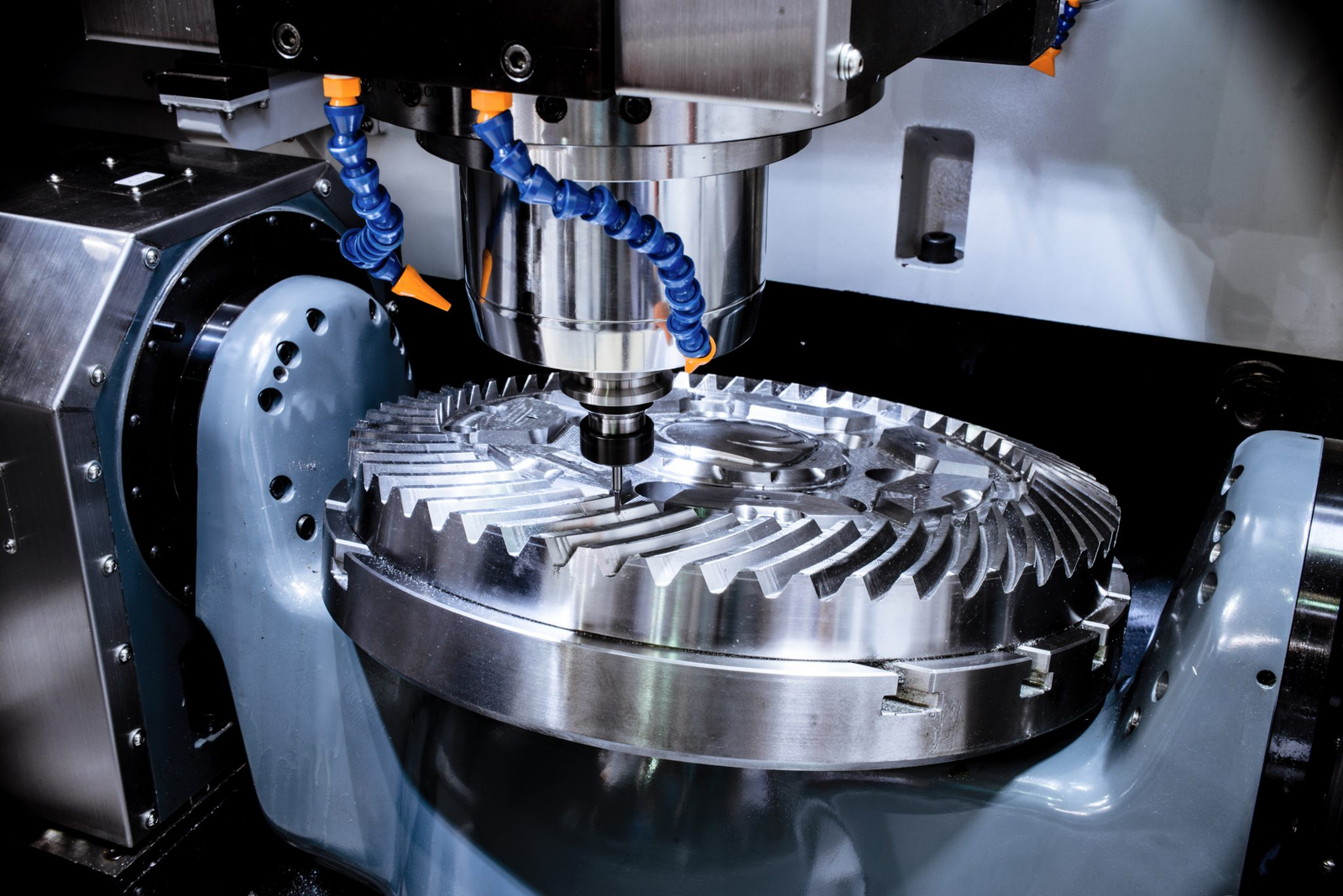

Tooling for Precision Machining

As production volumes increase, even small improvements in tooling efficiency can result in significant cost savings over time.

Prototype Tooling Approach

Prototype machining typically relies on standard tooling and minimal fixturing. The goal is to get the part machined with as little setup effort as possible.

Common prototype tooling practices include:

- Use of general-purpose end mills and drills

- Simple vises or modular fixturing

- Limited concern for tool life optimization

- Manual intervention to correct minor issues

This approach supports rapid change. If the design changes, the setup can be adjusted quickly without scrapping dedicated fixtures or tools.

Production Tooling Strategy

Production machining demands tooling that supports repeatability and efficiency. Tools and fixtures are selected and designed to hold parts consistently while minimizing setup time and variation.

Production tooling strategies often involve:

- Dedicated fixtures or pallets

- Custom soft jaws or locating features

- Tool selection optimized for long life and consistent performance

- Redundancy planning for critical tools

Although this level of tooling requires upfront investment, it reduces variability and lowers cost per part over the full production run.

Process Stability Requirements

Prototyping allows for trial and error. Operators can adjust offsets, tweak feeds, or rerun operations to achieve acceptable results. In production, this level of adjustment is not sustainable.

Stable production processes require:

- Predictable cutting forces and tool wear behavior

- Consistent part clamping and location

- Defined setup procedures that can be repeated across shifts

- Minimal dependence on operator judgment

Process stability ensures that parts remain within tolerance even as tools wear and machines run for extended periods.

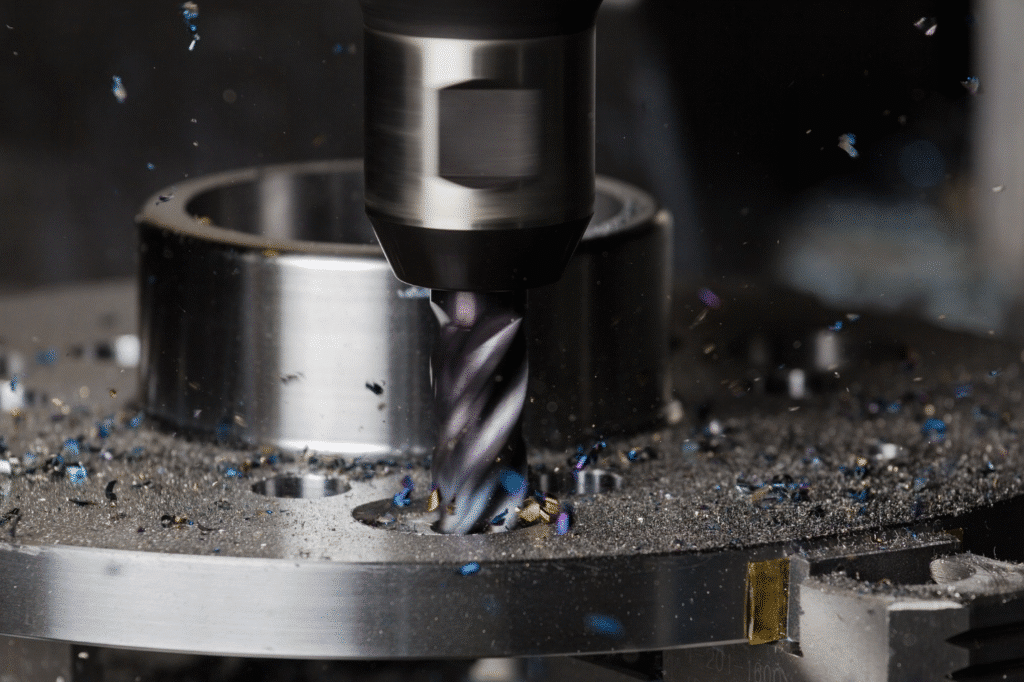

CNC Programming Differences

Programming strategy changes significantly between prototyping and production. Prototype programs are often simple and conservative, prioritizing reliability over efficiency.

Production programs are more refined. They focus on:

- Optimized tool paths to reduce cycle time

- Balanced cutting loads to extend tool life

- Reduced air cutting and unnecessary movements

- Consistent entry and exit strategies

These programs are tested and refined to ensure they run the same way every time. Once validated, changes are minimized to protect stability.

Tool Wear and Maintenance Planning

In production, tool wear becomes a predictable variable that must be managed. Ignoring it leads to dimensional drift and surface finish degradation.

Effective production planning includes:

- Defined tool life limits

- Scheduled tool changes

- Monitoring of wear on critical tools

- Documentation of tooling performance

By treating tooling as part of the production system rather than a consumable afterthought, teams maintain quality while controlling long-term costs.

Lead Time, Workflow, and Smooth Transition to Production

Lead time expectations and workflow structure change significantly when moving from prototyping to production. Prototyping emphasizes fast response and minimal planning. Production requires coordination across engineering, machining, quality, and supply chain functions. Without a structured transition, teams often experience delays that could have been avoided with better preparation.

A smooth scale-up depends on treating production as a planned phase rather than an extension of prototyping.

Lead Time Differences

Prototype lead times are usually short because decisions are made quickly and processes are simplified. Parts are often machined as soon as the design is available, with minimal documentation or review.

Production lead times are longer by design. Time is required for:

- Detailed process planning

- Fixture and tooling preparation

- Program verification and test runs

- Quality planning and inspection setup

While this preparation increases upfront lead time, it prevents disruptions during full production.

Workflow Structure

Prototype workflows are informal and flexible. Engineers, machinists, and designers often work closely, making changes in real time. This communication style supports fast iteration but does not scale well.

Production workflows rely on defined handoffs and documentation. Responsibilities are clearly assigned, and changes follow controlled procedures. This structure reduces variability and ensures consistency across teams and shifts.

Documentation Requirements

Documentation expectations increase significantly in production. Prototypes may be machined with incomplete drawings or informal notes, especially during early design stages.

Production requires complete and unambiguous documentation, including:

- Finalized drawings with defined tolerances

- GD and T where applicable

- Approved material specifications

- Inspection criteria and acceptance standards

Clear documentation reduces interpretation errors and supports repeatable manufacturing.

Design for Manufacturability Refinement

Design for manufacturability becomes critical during the transition to production. Features that were acceptable in prototypes may cause inefficiencies or quality issues at scale.

DFM refinement often focuses on:

- Simplifying geometry to improve tool access

- Reducing unnecessary tight tolerances

- Standardizing features where possible

- Aligning design intent with machining capability

Addressing these issues before production prevents costly late-stage changes.

Role of Pilot Runs

Pilot runs serve as a bridge between prototyping and full production. They expose issues that do not appear when making a small number of parts.

A pilot run helps teams:

- Validate tooling and fixturing under real conditions

- Confirm cycle time estimates

- Evaluate surface finish and dimensional consistency

- Refine inspection and quality checks

Lessons learned during pilot runs allow adjustments without disrupting full-scale production.

Communication and Feedback Loop

Effective transition relies on continuous communication between design, machining, and quality teams. Feedback from prototype machining should directly inform production planning.

A strong feedback loop ensures that:

- Known issues are addressed before scale-up

- Production settings reflect real machining behavior

- Design changes are documented and controlled

When this loop is maintained, teams avoid repeating mistakes and move into production with confidence.

Conclusion

CNC machining is highly effective for both rapid prototyping and production runs, but success depends on understanding how requirements evolve between these stages. Prototyping prioritizes speed, flexibility, and learning, while production demands control, repeatability, and cost efficiency. Differences in tolerances, surface finish, material selection, tooling strategy, and workflow are not incremental. They represent a fundamental shift in how machining decisions are made and evaluated.

Teams that plan this transition deliberately reduce risk as volumes increase. By refining design intent, stabilizing processes, investing in appropriate tooling, and validating decisions through pilot runs, CNC machining can scale smoothly from early concepts to reliable production. Treating prototyping and production as connected but distinct phases leads to better quality, lower costs, and faster time to market.