Choosing the right CNC machining process is one of the most important decisions an engineer makes when designing parts with complex geometry. The method you select directly influences the accuracy you can achieve, the cost of production, and whether the final component can be manufactured without design changes. When features like deep pockets, mixed radii, tight tolerances, or compound curves enter the picture, machining strategy becomes just as important as the CAD model itself.

This article breaks down how milling, turning, and multi-axis machining perform when the geometry becomes challenging. By examining how each process removes material, where each one excels, and the limitations that matter in real production environments, you can match your part to the most efficient and reliable method. The goal is to simplify your decision-making and give you a clear framework that avoids unnecessary complexity while protecting both manufacturability and quality.

Understanding the Three Core Processes

Before comparing machining strategies, it helps to understand how each process removes material and why certain shapes are naturally suited to one method over another. Milling, turning, and multi-axis machining all follow the same basic principle of subtractive manufacturing, yet the orientation of the tool and workpiece determines the type of geometry that can be produced efficiently. Once you recognize these differences, selecting the right process becomes far more straightforward.

CNC Milling Overview

Milling uses a rotating cutting tool to remove material as the workpiece remains fixed or moves along linear axes. This setup allows the tool to approach the part from different directions and generate a wide range of flat and contoured shapes. Most shops rely heavily on milling for prismatic components because of its precision and flexibility.

Best applications for milling include:

- Pockets, slots, and flat surfaces

- Orthogonal geometries with defined edges

- Contours, step features, and shallow cavities

Milling works well for features that require clean edges and controlled depths. However, it becomes less effective when the design includes deep cavities or tall walls, where tool deflection and vibration become risks. Long tools may be required to reach certain areas, which reduces rigidity and accuracy. Undercuts also create challenges unless the machine includes additional axes or specialized tooling.

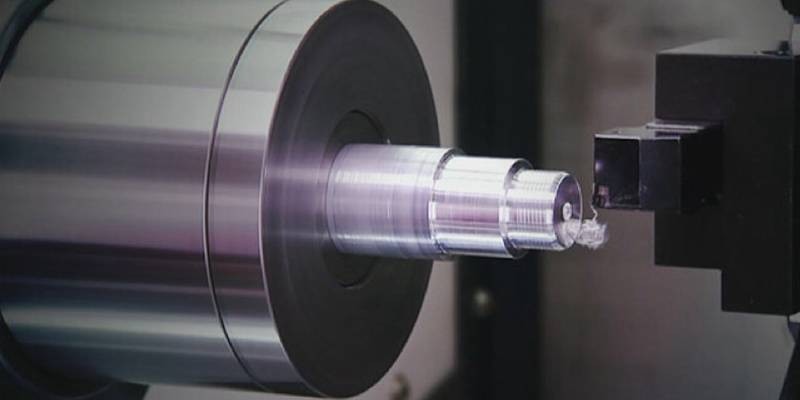

CNC Turning Overview

Turning removes material by rotating the workpiece while a stationary or linearly moving tool cuts along the outer or inner diameter. The rotational motion makes this process highly efficient for creating symmetric profiles with strong dimensional consistency. Turning machines are used extensively for shafts, bushings, sleeves, and similar parts where circular geometry dominates.

Turning is ideal when the part includes:

- Cylindrical or conical shapes

- Uniform rotational features

- Threads, grooves, or precision diameters

The main limitation appears when a part includes non-axisymmetric geometry. Features like flats, square pockets, or irregular contours are not well-suited to pure turning. These require a secondary milling operation or a hybrid mill-turn system. Designers must also avoid combining complex prismatic features with turning-only workflows because this increases setups and reduces efficiency.

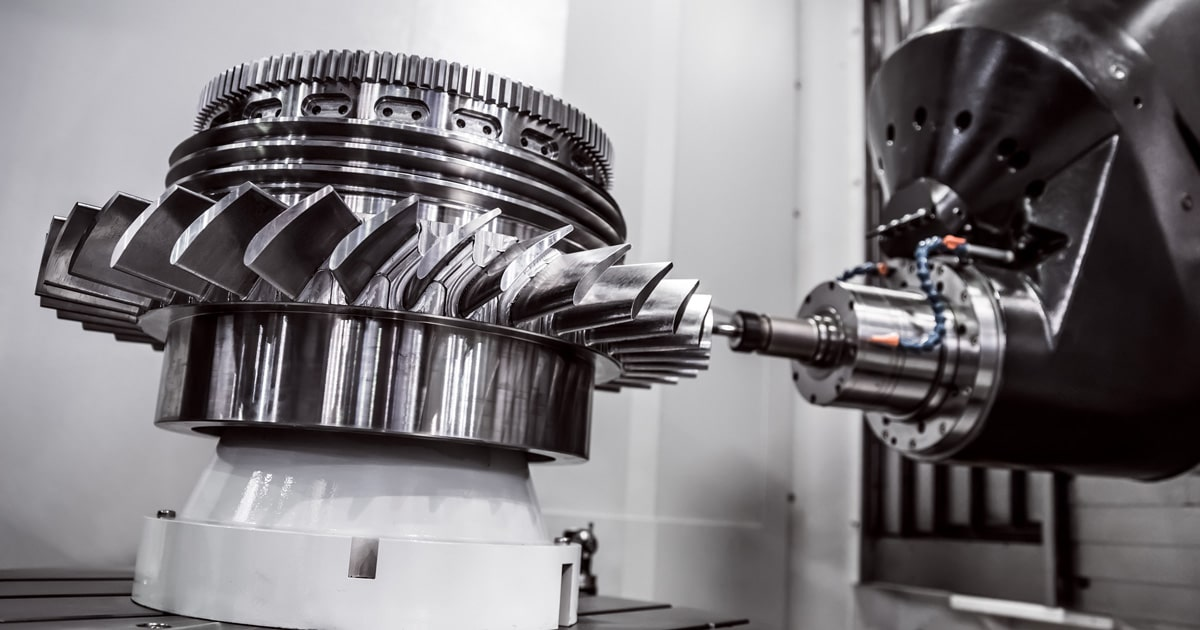

Multi-Axis Machining Overview

Multi-axis machining expands capabilities by allowing the tool to rotate and tilt while moving around the part. This orientation control lets the tool maintain optimal cutting angles, reach difficult surfaces, and avoid excessive tool length. Multi-axis systems are essential for parts with compound curves, organic transitions, and deep features that cannot be accessed from a single direction.

Multi-axis machining is suited for:

- Undercuts and recessed areas

- Smooth freeform surfaces

- Complex brackets, turbine components, and medical implants

This capability comes with a higher cost due to machine complexity, longer programming time, and increased setup requirements. Skilled CAM programming is necessary to generate smooth toolpaths and maintain collision safety. However, when the geometry demands continuous reorientation or seamless transitions, multi-axis machining often becomes the most practical approach.

Key Criteria for Process Selection

Choosing the correct machining method begins with understanding the geometry, but the decision extends beyond shape alone. Engineers must also weigh tolerance needs, surface finish, tool accessibility, part scale, and overall production cost. These factors often interact, and a process that suits the geometry may still be inefficient or expensive when evaluated across the full manufacturing workflow. A structured evaluation helps prevent unnecessary complexity and ensures that the selected method aligns with quality and cost expectations.

Geometric Complexity

Geometry remains the first filter that determines which machining process is the most efficient. Parts with clean, prismatic shapes fall naturally into milling workflows, while circular and symmetric profiles match the strengths of turning. When a single part contains mixed features or smooth organic surfaces, a multi-axis machine may be required to maintain tool access and surface integrity.

General guidelines for matching geometry to process include:

- Simple prismatic or planar shapes are most efficient on 3-axis milling

- Cylindrical profiles work best on turning centers

- Blended curves, compound angles, and mixed surfaces often require 4 or 5-axis machining

Selecting based solely on geometry avoids overprocessing and reduces the risk of complex setups that add cost without improving performance.

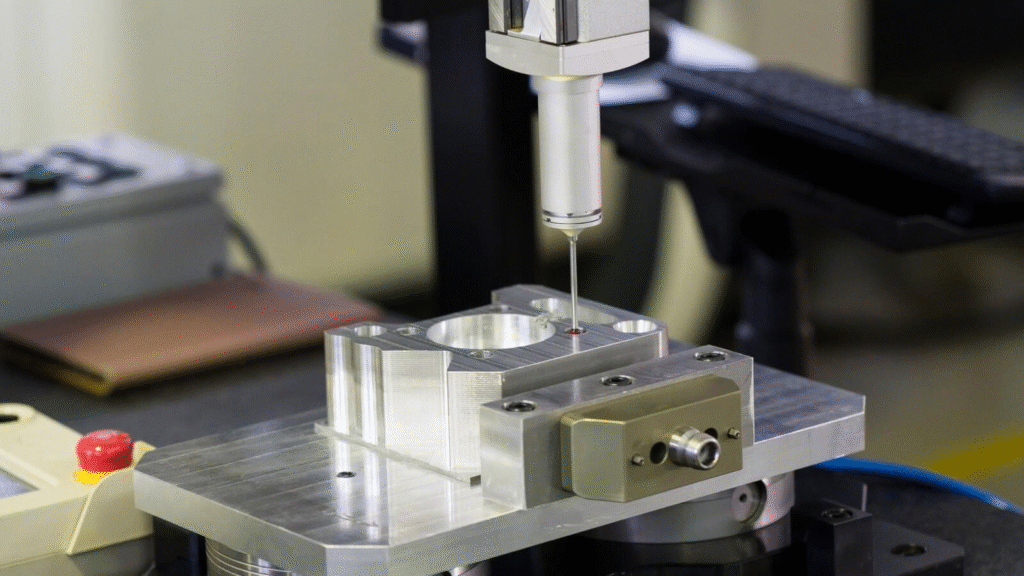

Tolerances and Surface Finish

Tolerance requirements influence process choice because each method offers different strengths. Turning naturally produces excellent circularity and straightness due to the rotational motion of the workpiece. Milling provides predictable flatness and dimensional control across planar surfaces, which is important for housings, brackets, and structural components. Multi-axis machining improves alignment by reducing the need for repositioning.

Key considerations include:

- Turning achieves high-quality diameters, smooth finishes, and consistent roundness

- Milling maintains uniform flatness, depth accuracy, and repeatable planar features

- Multi-axis systems eliminate multiple setups, which protects positional accuracy between complex features

Understanding which features require the tightest control helps determine when upgrading to a more advanced machine is justified.

Tool Accessibility and Reach

Even well-designed parts become difficult to machine if the cutting tool cannot reach certain features without losing rigidity. Deep pockets, tall walls, and narrow openings often lead to long tool lengths and increased deflection. This results in vibration, reduced surface quality, and lower dimensional accuracy. Multi-axis machining can reposition the tool to create shorter, more stable cutting paths.

Important factors to evaluate include:

- Risk of tool deflection in deep or narrow areas

- Whether angled or hidden faces can be reached without secondary operations

- The possibility of reorienting the tool using additional axes to shorten the tool length

Tool accessibility directly affects cycle time and finish quality, so resolving access issues early improves manufacturability.

Production Volume and Cost

Production scale influences the economics of machining. Turning is often the fastest and most cost-effective method for round parts, especially when producing medium or high volumes. Milling is practical for a wide range of batch sizes but becomes more expensive when multiple fixturing steps are required. Multi-axis machines carry higher hourly rates but can offset that cost by reducing setups and simplifying workflows for complex parts.

Key cost considerations include:

- Turning provides rapid cycle times for rotational components

- Milling supports flexible, low to medium production volumes

- Multi-axis machining reduces manual handling and fixture changes at a higher machine-hour cost

Evaluating both geometry and production scale ensures that the chosen machining strategy meets cost targets without sacrificing quality.

Trade-Offs Between Milling, Turning, and Multi-Axis

Each machining process brings specific strengths to the table, but none of them solve every problem. Milling offers versatility but is slower than turning for circular profiles. Turning excels in speed and precision for rotational parts, but cannot handle prismatic or angled features without secondary operations. Multi-axis machining provides the highest geometric freedom, although it requires greater programming skill and higher machine costs. Understanding these trade-offs helps engineers select the process that delivers the best balance of capability, efficiency, and cost for the geometry at hand.

Speed vs Complexity

Different machining processes handle complexity and material removal very differently. Turning maintains some of the highest material removal rates because the entire workpiece rotates, allowing tools to cut efficiently along the diameter. Milling slows down as features become deeper or require frequent tool changes. Multi-axis machines handle intricate geometry but spend more time on positioning, orientation, and collision checks.

Key comparisons include:

- Turning provides rapid cutting performance for circular components

- Milling slows when features vary in depth, angle, or tool type

- Multi-axis machines require longer setup and toolpath verification for complex surfaces

Selecting a process that matches the complexity of the design avoids unnecessary cycle time and reduces the risk of machining errors.

Cost vs Capability

Cost structure varies significantly across machining methods. Three-axis milling and standard turning centers offer the lowest machine-hour rates due to simpler hardware and faster setups. Turning is particularly cost-effective because fewer tool changes and movements are required. Multi-axis systems increase capability but come with higher operational and programming costs. Engineers must evaluate whether the additional capability is needed or if simpler equipment can achieve the required geometry.

Important cost considerations include:

- Three-axis milling is affordable for most prismatic designs

- Turning minimizes cycle time and tool wear for shafts, bushings, and threaded parts

- Five-axis machining increases cost per hour but reduces fixtures, setups, and manual intervention

Balancing these factors prevents overuse of advanced equipment when a simpler process can produce the required features.

Accuracy vs Re-Orientation

Accuracy is influenced not only by the machine itself but also by how many times a part needs to be repositioned. Three-axis milling often requires multiple setups for features that cannot be reached from a single direction. Each reorientation introduces the potential for small alignment errors, especially in parts with tight tolerances between faces. Turning avoids this issue for round geometry because the part remains centered throughout. Multi-axis machining preserves accuracy by maintaining a single established origin while reaching many faces without repositioning.

Key points to consider include:

- Re-fixturing in three-axis milling increases the risk of misalignment

- Turning maintains a consistent centerline for all rotational cuts

- Multi-axis machining enables complex feature alignment within one continuous setup

Choosing the process with the fewest required setups helps protect dimensional relationships between critical features.

Case Examples by Part Complexity

Real examples make it easier to understand how geometry influences the choice of machining method. Engineers often encounter parts that look suitable for a simple process at first glance, but specific features reveal the need for a more capable approach. By evaluating typical components across different complexity levels, it becomes clearer when to rely on milling, turning, multi-axis machining, or hybrid systems. These examples also highlight how the selected process impacts accuracy, cost, and total machining time.

Prismatic Housing with Pockets and Slots

A prismatic housing is a common component in mechanical assemblies, and its features are usually well-suited to standard milling workflows. The design often includes flat faces, machined pockets, mounting holes, and shallow cavities that do not require tool access from multiple angles. A three-axis mill can reach most areas with simple strategies and predictable toolpaths. If the housing includes features that wrap partially around the sides, a four-axis machine can rotate the part to provide better access without complex fixturing.

Why milling is the best fit:

- The geometry is dominated by planar surfaces and orthogonal edges

- Most pockets and slots are accessible from above

- The features do not require deep reach or continuous tool orientation

- Surface finish and dimensional accuracy can be achieved with standard tooling

This type of part benefits from low setup time and consistent repeatability, making three-axis or four-axis milling both practical and cost-effective.

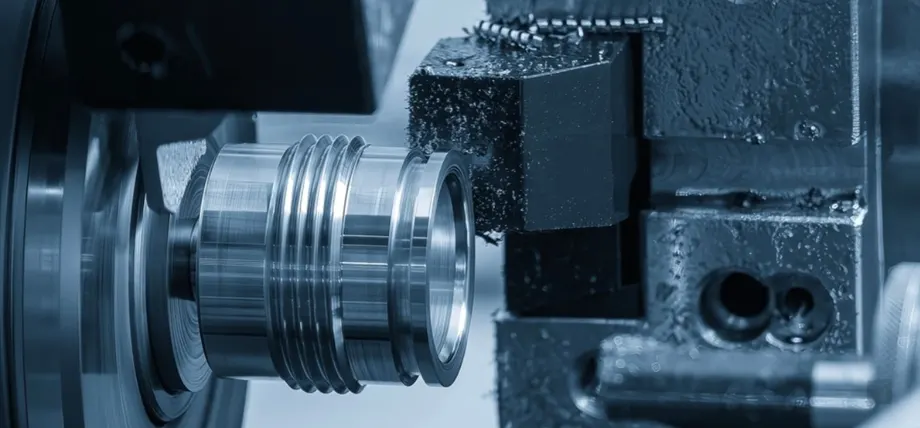

Cylindrical Shaft with Grooves and Threads

A shaft is a natural candidate for turning because its shape revolves around a central axis. Turning allows the machine to cut diameters, grooves, shoulders, chamfers, and thread profiles with high precision. Features such as keyways or cross holes can be added later using a secondary milling operation if needed. The rotational symmetry ensures stable cutting conditions and excellent tolerance control along the length of the part.

Why turning is the leading option:

- The geometry aligns directly with the rotational capabilities of a lathe

- Grooves and threads are created quickly and accurately

- Surface finish along the diameter is smooth and uniform

- Tight tolerances on runout and concentricity are easier to maintain

A combination of turning and light milling may be used if additional prismatic features exist, but pure turning remains the core process.

Complex Bracket with Undercuts and Compound Curves

A bracket with curved transitions, angled faces, and hidden features presents challenges for standard milling. Many surfaces cannot be reached from a single orientation, and deep cuts can cause tool deflection if attempted on a three-axis machine. A five-axis machine provides continuous control of tool orientation, allowing the cutter to approach surfaces from angles that maintain rigidity and reduce overhang.

Why is five-axis machining required?

- Undercuts and recessed regions need multi-angle access

- Compound curves require smooth interpolation across multiple axes

- Several surfaces cannot be aligned for vertical or horizontal cutting

- Fewer setups reduce the risk of misalignment across complex features

This approach preserves dimensional relationships and creates a much higher quality finish on organic or blended surfaces.

Hybrid Geometry: Flat Faces and Cylindrical Sections

Some components combine circular features with flat surfaces, such as shafts with mounting flats, stepped housings, or parts with both turned and milled sections. Producing these parts efficiently often requires both turning and milling. A mill-turn machine can complete the entire part in a single setup, which improves accuracy and reduces handling time. This eliminates the risk of misalignment that occurs when a part is transferred between multiple machines.

Why a mill-turn system is ideal:

- It handles both rotational and prismatic features without repositioning

- Diameters and threads are turned accurately, while flats and slots are milled

- A single setup maintains consistent feature alignment

- Total cycle time is reduced by avoiding machine transfers

Hybrid machines provide the best balance when a part does not fit neatly into one category.

Practical Decision Framework for Engineers

Selecting the right machining method becomes much easier when guided by a structured evaluation. Engineers can rely on a clear framework instead of intuition alone, which reduces the risk of choosing a process that is either overly complex or insufficient for the geometry. A systematic approach ensures that all critical factors are considered, including feature types, tolerance requirements, accessibility challenges, and cost implications. This section outlines a practical method for analyzing a part and determining the most efficient manufacturing strategy.

Step-by-Step Process Selection Guide

A repeatable selection method helps streamline decisions across projects and teams. Instead of viewing the machining process as an afterthought, this guide integrates manufacturing considerations into the design stage, which prevents costly revisions later. Each step focuses on identifying the core geometric and functional needs before matching them to the appropriate process.

Key steps to follow include:

- Identify the dominant geometry by evaluating whether the part is primarily prismatic, cylindrical, or mixed

- Map each feature to the process that produces it most efficiently to highlight potential combinations

- Review tolerance critical areas and determine whether the chosen process can reliably meet them

- Assess tool access for deep pockets, angled faces, or narrow regions that may cause rigidity issues

- Estimate the number of setups and fixture changes required to complete the part

- Compare machine-hour cost with expected improvements in accuracy, cycle time, and workflow efficiency

By moving through these steps, engineers can justify process choices with confidence and clarity.

When to Upgrade to Multi-Axis

Multi-axis machining should be used when a part demands capabilities beyond the reach of standard milling or turning. The decision should be driven by necessity rather than convenience, since multi-axis equipment requires higher programming skills and cost. However, when geometry complexity increases, multi-axis machines often become the most efficient and reliable way to maintain accuracy and surface quality.

Situations where upgrading makes sense include:

- Multiple orientations are required and cannot be achieved with simple fixturing

- Deep cavities or hidden features produce excessive tool overhang on three-axis machines

- Complex curves, organic transitions, or sculpted surfaces need continuous tool orientation

- Consistency across several intricate features is critical and must be maintained within one setup

Understanding these triggers helps avoid both underuse and overuse of advanced equipment.

When Three-Axis or Turning Is Enough

Not every design benefits from advanced machining technology. In many cases, simpler processes offer faster production, lower cost, and sufficient accuracy. Recognizing when a straightforward method is appropriate prevents unnecessary complexity and keeps manufacturing budgets under control.

Three-axis milling or turning is often the best choice when:

- The geometry is simple, symmetric, or dominated by planar or cylindrical features

- Tight tolerances apply only to round elements that can be turned accurately

- Budget constraints require minimizing machine-hour cost without compromising quality

- All features can be reached through standard orientations and tool paths

By selecting the simplest viable method, engineers maintain efficiency while meeting design intent.

Conclusion

Choosing the right CNC machining process begins with a clear understanding of the geometry, tolerance needs, and accessibility challenges within a part. Milling, turning, and multi-axis machining each provide unique strengths, and the most effective method depends on how well those strengths match the features being produced. By evaluating factors such as feature orientation, required surface finish, setup complexity, and the stability of the cutting process, engineers can select a method that supports both accuracy and manufacturability.

A structured decision process helps avoid overspending on advanced machines when simpler methods can achieve the same result, while also highlighting situations where multi-axis capability is essential for producing complex geometry within a single setup. When geometry, cost, and quality considerations are aligned, the chosen machining strategy delivers predictable performance, reduced lead time, and a more efficient manufacturing workflow.